Gold: A Different Asset Class

To which asset class does gold really belong...?

WHAT KIND OF "asset class" includes gold – and just why are private investors Buying Gold to push it nearly 25% higher in the last three months alone?

Dubbed the No.1 "diversifier" by serious analysts and wealth managers alike, gold clearly stands outside the three asset classes held by most private investors.

- Bonds: Gold pays you no interest, not unless you lend it in return for a yield (rather than lend it in ignorance via an "unallocated" gold account). Nor does gold promise to repay your original capital at some point in time. There is no maturity date. But then, since gold is no one's debt to repay, the threat of default is zero.

- Stocks: Gold has nothing in common with equities either. It employs no staff, no board of directors, and gives no quarterly earnings report. It doesn't make anything or provide a service beyond being yellow, shiny and rare.

- Real Estate: Nor is gold anything like commercial or residential property. Even if you did rent it out, you still couldn't extend it or add a marble-topped plinth in the kitchen. Gold requires no upkeep (it's virtually indestructible), and there's no income-tax to pay, because there's no income to tax.

No wonder Gold Bullion Investment fell out of favor during the property, bond and securities boom that got started as the runaway inflation of the 1970s started to fade.

Gold didn't offer a dividend, yield or interest payment (it still doesn't). So as the soaring cost of living began to slowdown, investments offering to pay a regular income became more attractive. Those investments like gold that pay you nothing just weren't wanted. Nor could gold buy you anything either! This dumb lump of metal lost all official links to the value of money when Richard Nixon finally killed the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971. Refusing to exchange Dollars for gold, Nixon made Buying Gold a pure speculation – rather than a way of holding cash.

More than that, gold actually costs you money to store and insure. A real sucker's trade, therefore, gold sank once the panic of the late '70s inflation slipped into memory and everything else shot higher.

But now gold has turned higher again. While trying to figure out why, you might also like to know just what kind of an asset class you're getting into if you Buy Gold today.

Cut free from the world's monetary system, gold's not listed as a currency by Bloomberg or Reuters. Instead, gold has come to be classed as a commodity – "an article of commerce or a product that can be used for commerce" according to the National Futures Association.

Does it make sense to lump gold along with cocoa, orange juice, lean hogs and zinc? "The simplest definition of commodities is that they are raw materials," notes Katharine Pulvermacher in a 2005 paper for the World Gold Council – and raw materials, by definition, are used to make other products: Wheat into bread; copper into electrical wiring; crude oil into gasoline; hogs into bacon...gold into...?

Well, gold into what?

The quick answer is jewelry. The wrong answer is microchips. An ever-more common confusion is that gold bought today will make you a capital gain tomorrow. (After all, gold has risen nearly 25% inside three months!)

Another popular myth is that gold makes a cheerful partner for base-metal and oil traders, happily rising and falling in line with the price of crude, copper and zinc. The great bull market of the late '70s certainly mirrored surging prices for energy inputs. But just because dolphins swim, that doesn't mean they're pilchards – and the parallels between Gold Prices and the broader commodity markets is by no means perfect.

In the twenty years to 2006, weekly price movements in gold showed a correlation of only 0.1 with the weekly move in commodity prices according to data from the Swiss National Bank (SNB). It would be nearer 1.0 if gold and commodities moved together.

What's more, the correlation has "varied heavily within the period," notes the SNB, "and despite similarities in [broad] price movements, the gold market has a number of distinct features."

Not least amongst gold's distinct features is the fact that it's (virtually) indestructible. That means there now exists an enormous supply of gold outstanding above ground – and this makes gold as unlike crude oil as you can get.

Gold does not get burnt up once it's been mined and refined. Instead, it just sits there – not doing anything, but not vanishing either. That makes it very different from oil.

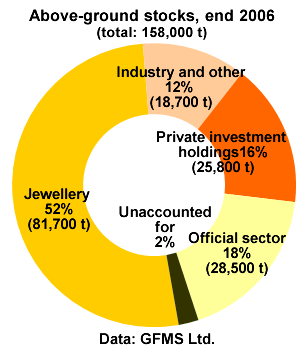

All told, says the educated guess-work by GFMS Ltd., the widely-respected London consultancy, there were some 158,000 tonnes of gold sitting above-ground by the end of 2006.

Only 12% was being used in industry. Meaning that just one ounce in eight had found its way into people's teeth, home-pregnancy testing kits, and mobile cell phones.

Yes, the proportion of new gold going into electronics and other industrial end-uses is rising; it will account for 19% of all the extra gold mined and supplied to the world market in 2007 say the analysts at Virtual Metals in London. That figure has risen from 14.5% in 2002.

But the vast bulk of the world's gold is still not "consumed" by industry, even if new uses in nanotechnology and cancer treatments are regularly announced by the gold mining industry's marketing and lobby group, the World Gold Council. This sets it apart from both silver and the platinum-group metals, all of which are as heavily used by industry – if not more so – than they are by jewelry and investment buyers.

This relative lack of industrial value also separates the demand for gold almost entirely from the flux of economic growth. Price patterns come and go, but a 27-year study in 2003 – covering both the bull market of the 1970s and the long slump that followed – found that:

- Gold showed "no statistically significant correlation" with changes in big-picture economic trends such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), inflation or interest rates;

- US stocks and bonds, in contrast, were linked to changes in the economy;

- Other commodities – "such as aluminum, oil and zinc" – also showed a much stronger correlation with economic changes than did gold;

- These other commodities also showed a greater connection than gold to the returns earned from stocks and bonds.

"These results support the notion that gold may be an effective portfolio diversifier," concluded the study's author, Colin Lawrence, visiting professor at Cass Business School in London. He noted "the lack of correlation between returns on gold and those on financial assets such as equities."

Yet Lawrence still called gold a "commodity", a word that most people take to mean – in its everyday sense – something consumed as an industrial input or used as a raw product in our homes. The vast bulk of the world's gold, in contrast, does not have this kind of economic purpose. It now exists in gold jewelry, central-bank vaults, and private investment portfolios instead.

Add them together, and these physical gold hoarders – central banks, private investors and jewelry owners – hold 86% of all the gold ever mined between them. Whatever "use" they believe they're making of gold, it's clear that their consumption does not destroy the metal.

While the long-term historical and traditional gold-buying motives of central bankers and jewelry owners deserves it's own study, the Gold Market is clearly moving higher on a wave of investment demand right now.

"There is so much uncertainty around and if you’re looking for a basic store of value what else do you choose?" asks Peter Hambro, head of the eponymous gold-mining company listed on the London Stock Exchange but hard-at-work in Russia.

"All currencies seem to be in a degree of flux. It is about how much currencies will devalue against gold. The Dollar will probably fall further – so gold could reach the record high levels of the 1970s of $850 an ounce."

Hambro's reference to currencies is telling. RBC Capital Markets trade the metal on their currency, rather than commodity desks. "The right way to trade gold is as a foreign currency, not as a commodity," agreed Steven Mathews, commodities strategist at Tudor Investment Corp. in a 2003 study for the London Bullion Market Association's Alchemist magazine.

Mathews compiled data showing "days of supply" for each of the most heavily traded commodities. Stockpiles of soybean meal, for instance, stood ready to meet 2.5 days of demand on average.

Natural gas inventories held on average 37.5 days of supply. Silver – used in batteries, soldering, catalysts, photography and electrical switches, as well as jewelry – had 105 days of supply backed up. Coffee had 216 days...

And gold stood ready to meet more than 7,019 days-worth of demand. The nearest ready-at-hand stockpile was for platinum at around 15 months. But that pales next to gold's 19 years of supply.

"It’s fair to say that nothing else even comes close," Mathews concluded, "[so] I don’t classify gold as a commodity at all. Obsessively following mine production and demand are valuable only as a way of anticipating actions of other traders. Gold [instead] trades as a form of foreign exchange."

If gold does belong to the currency asset class, then the "stateless currency" is clearly beating all the rest in the first decade of the 21st century, outpacing Euros, Rupees, Chinese Yuan and Sterling. It touched a new all-time high vs. British Pounds on Friday 2 Nov., even as Sterling made a new quarter-century high vs. the US Dollar.

But gold – unlike the rest of the world's tradable currencies – cannot raise or cut its interest rates to attract or dissaude currency speculators. Gold pays no interest whatsoever, remember. And while that might mean it has something in common with the Japanese Yen, it has nearly tripled against that currency so far in this bull market. It has also outperformed the three key asset classes that still sit in most people's investment portfolios – and "the investment motive is a much more important driver in the gold market than in the market for other commodities," as Philipp Hildebrand, vice-chairman of the Swiss National Bank pointed out in a 2006 speech.

Given that gold doesn't pay you anything in yield, interest or dividends – and that it does not have any real industrial value – the "investment motive" for gold can only be explained as desire to quit other assets. Or at least, to hold an asset entirely free from what drives other asset markets up and down.

That's what happened during the 1970s.

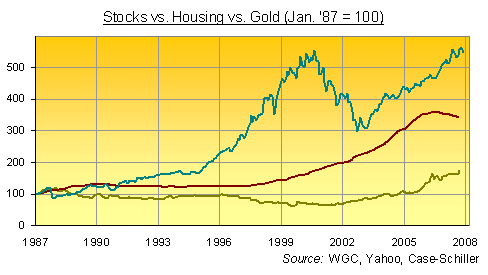

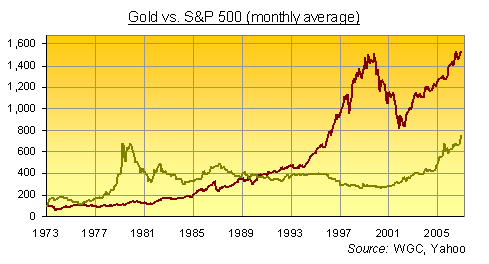

During the last great bull market in gold, between 1970 and 1980, a portfolio spread evenly across US stocks and bonds would have lost 1.6% per year on average. Gold's annual gains, meantime, averaged 19.9%.

In real terms – allowing for inflation – the S&P 500 index actually dropped an average of 4.2% year-on-year. Gold Prices, on the other hand, out-stripped the soaring cost of living by more than 29% per year.

For bond investors, the real yield offered by US Treasuries collapsed during the 1970s. On the 10-year note, real yields averaged less than 0.4% above inflation. Indeed, they slipped below zero – signaling a loss of purchasing power – for two years starting in Sept. 1973, and again from Sept. 1978.

Gold, meantime, rose 15 times over.

But "the price for this 'insurance function'," as Philipp Hildebrand of the Swiss National Bank went on in that 2006 speech, "is reflected in the fact that gold is less profitable in the long term than other financial assets."

Gold certainly lost out to other financial assets during the 1980s and '90s. As bond yields rose above falling inflation, the S&P soared 12 times over. Gold Prices, in contrast, dropped 3% of their Dollar value every year for two decades on average. Between 1994 and 2000 alone, gold dropped by one-quarter. An equal mix of US equities and bonds, on the other hand, would have given you 10.7% returns annually on average.

Over the last seven years, however, the "insurance function" of gold has paid off handsomely – and for the second half of this period, insurance wasn't even needed! Between New Year's Eve 1999 and the start of 2003, the S&P averaged a loss of 15% per year. Gold rose by more than 7.9% year-on-year.

Since then, the S&P has risen by more than two-thirds. Yet gold has also continued to rise, gaining 125% in the last four year even after the Tech-Stock Crash was finished.

Has gold's "insurance function" been cancelled? Just what are private investors Buying Gold for today if they don't need protection from falling equities and crumbling bonds?

Well, perhaps the gold market says investors are looking for protection against falling bond, real estate and equity values – as well as a falling US Dollar and slumping US economy.

So they are buying protection ahead of time. And to do that, they're Buying Gold – a wholly different asset from everything else.

Email us

Email us